A New Kind of Old

Brian McLaren’s twists and turns are too subtle for a generation of Christians left vulnerable by ministers who don’t teach the Bible. Erich Rauch of American Vision is very helpfully working his way through Brian McLaren’s latest book, A New Kind of Christianity.

“Due to the strong influence that he has as a “pastor to pastors,” any time McLaren releases a new book it is a pretty big deal within the walls of the church. And because he is giving voice to concerns that many pastors and church leaders have expressed and thought about themselves, his writings indirectly resonate from American pulpits nearly every Sunday morning. His newest book, A New Kind of Christianity, claims to describe what Christianity might look like if it were “not afraid of questions.” Questions are a really big part of McLaren’s ministry. In fact, the subtitle of the book is: “Ten Questions that are Transforming the Faith.” Now I am certainly in favor of questions; I think that far too many people are far too easily satisfied with conventional ways of thinking and doing things. I agree with McLaren that questions can effect change; but I disagree with him and his book’s subtitle because it’s not the questions that cause the progress, it’s the answers. And unfortunately, this is where McLaren is his weakest.”

Rauch carefully untangles the truth from the distortions in McLaren’s questions, and demonstrates the false assumptions that lead this modern thinker astray when it comes to the Bible.

“While [McLaren's position] may have all the trappings and appearances of being a humble and contrite way of interpreting the Bible, the reality is that McLaren’s “new way” is nothing more than the “old way” of theological liberalism. He may claim that his way is neither conservative nor liberal, but he is only half-right; it is liberal to the core. McLaren seems to be under the impression that all liberal interpreters that came before him were looking for ways to “explain away” the text, but in actuality most theological liberalism is the result of trying to do exactly what McLaren is recommending: getting “into” the text, where God can speak to our modern sensibilities through His “ancient” words. This has always been a driving force behind theological liberalism: adapting the Scriptures to the contemporary culture, rather than the culture to the Scriptures. Without explicitly saying it, McLaren portrays conservatives as being crusty, old “Bible-thumpers” who don’t spend more than a second or two thinking about what the Bible actually says, and liberals as ones who want to take every opportunity to discredit the Bible as being untrue. With this (false) antithesis squarely in place, McLaren rides through the battle—with unstained uniform—as the keeper of the proverbial middleground; a sort of hermeneutical Rodney King, naively wondering why we can’t all just get along.

…McLaren makes the correct observation that both the conservative and the liberal ways of interpreting the Bible—at least as far as he has defined conservative and liberal ways to be—gives a great deal of authority to the interpreters themselves. This is undoubtedly true. In fact, this very thing was pointed out to Martin Luther when he was undertaking the task of translating the Bible into German. Putting the words of Scripture into the hands and imaginations of everyone makes everyone an interpreter and, in a sense, gives them power to “be as God,” deciding good and evil for themselves. Luther understood this, but also understood that Truth was worth the risk. Simply by reading McLaren’s book and his way of interpreting and understanding the Bible, I make myself a potential convert to his way of reading and understanding. In actuality, this is exactly what he wants. He wrote his book to influence his readers with his way. He says he is fed up with “careless preachers [who] use the Bible as a club or sword to dominate or wound, [who] discredit the Bible in a way that no skeptic can” (p. 69). I, too, am fed up with this, but I am not quite ready to follow McLaren in a wholesale abandonment of the historicity of the book of Job (for example) as being an “archetypal theological opera” (p. 95). An honest reading of Job seems to indicate that the events that it speaks of are real and actual, not literary devices that are inviting us into “conversation.” My dusty “conservative” hermeneutic may not sell as many books as McLaren’s new and updated liberal one, but, in truth, this is where the real heart of the “authority” question lies.

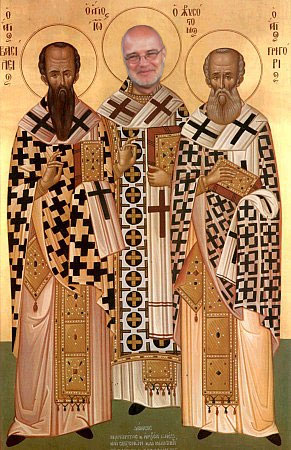

When McLaren—who is admittedly not a trained theologian—makes judgments about a particular book of the Bible’s overall meaning, he is exercising the very power over the text that he accuses conservatives and liberals of having. It is significant that McLaren has never been to seminary; he does indeed find details and connections in the Scripture that most seminary-trained men will blow right past in their surface-level search for doctrinal application. It is also significant that McLaren was trained in literature because he seems to be incapable of reading the Bible as anything other than a God-inspired (whatever that means to him) work of fiction. This is why I find it so fascinating that McLaren accuses the early church fathers of bringing Greek philosophy into their reading of the Bible, when in reality the fathers were reading the Bible the very way he claims to be recommending.”