The Art of Story

‘Stories are equipment for living.’ – Kenneth Burke

Blog gurus tell you never to blog “off brand,” but this one’s not as off as it might appear.

If you love the Bible and haven’t read Robert Alter’s The Art of Biblical Narrative, you really need to. One of the reasons for the Reading the Bible in 3D seminar in April was to help people understand that the tools they gain from watching quality movies and TV and reading good fiction should not be shelved when reading the Bible. Sadly, it seems most Christians really aren’t interested in understanding the Bible in a new way. They are taught by ministers who have little idea of what they are actually dealing with in the Bible, and the ministers were trained in Bible academies ruled by men without an ounce of the childlike imagination the Bible requires to be understood. Consequently they miss the beauty, the musical rhythm, the intricacies and the constant use of “plant and payoff”, all of which are understood by the best authors. This includes screen writers, who have to say everything the writer of a novel says but in less words. Robert McKee writes:

From inspiration to last draft you may need as much time to write a screenplay as to write a novel. Screen and prose writers create the same density of world, character, and story, but because screenplay pages have so much white on them, we’re often mislead into thinking that a screenplay is quicker and easier than a novel. But while scribomaniacs fill pages as fast as they can type, film writers cut and cut again, ruthless in their desire to express the absolute maximum in the fewest possible words. Pascal once wrote a long, drawn-out letter to a friend, then apologised in the postscript that he didn’t have time to write a short one. Like Pascal, screenwriters learn that economy is key, that brevity takes time, that excellence means perseverance. [1]

Aaron Sorkin has said that what got him hooked on writing was watching a play and being fascinated by the “music” of the dialogue. John Truby says that plot is not something you make up as you go along, and that all the best stories use the element of surprise. (If you are interested in the hard slog that is screenwriting, there’s a great interview with “script doctor” John Truby here.) In every case, the elements of wonder and surprise are what get people hooked. The Bible was completed two millennia ago, and it is still coming up with surprises. However, it is rarely taught this way, and plenty of good theologians are kicked out or ignored by the establishment because “mature” minds don’t understand story as art. At the heart of narrative surprise (the good ones, anyway) is the “plant and payoff” technique, which is the basis of typology, and I would argue that this is an application of God’s own Covenantal “forming and filling.” The writer plants a single seed which dies in the ground and later produces a harvest. (Here’s an article by a man who may have just lost his job for saying such things.)

One of the reasons I love cinema and good TV, from art house through well-written cable shows right down to blockbusters, is that good storytelling makes excellence possible in any genre. And the best storytelling, for me at least, involves the use of symbol. Lewis and Tolkien understood that the best way to comment on the real world is to view it from another one. All the visions of the Bible do this. They take place in the heavenly court, but of course what happens on the earth is the exposition of the compact types that come from the mouth of God.

I thought I’d lighten up for a bit and write some fiction (for my kids), but fiction with the pace and visual language of images on the screen. The only “world” I really know is Doctor Who, since I grew up with it. It’s one of those shows which had to rely on storytelling since the low budget meant the audience had to use their imaginations for much of what was going on anyway (and I find the fact that it never takes itself seriously very charming as well). It’s a show where anything can happen. When it’s terrible, it’s really terrible, but when it’s good, it’s a vehicle for commenting on the real world in a format that is infinitely flexible. Taylor Parkes writes:

Doctor Who is like pop music: it’s cheap, loud and trashy. And, as with pop music, these are not flaws but strengths – adding power and immediacy, validating everything. Enabling, from time to time, a peculiar transcendence, a particular kind of truth. And, as with pop music, trashiness is a hook, a way for Doctor Who to communicate big ideas without having to bore you; to encourage absolute mental freedom, with all those crazed audio-visual freakouts, all those mind-expanding trips into the abstract, and the absurd, and the extreme. [2]

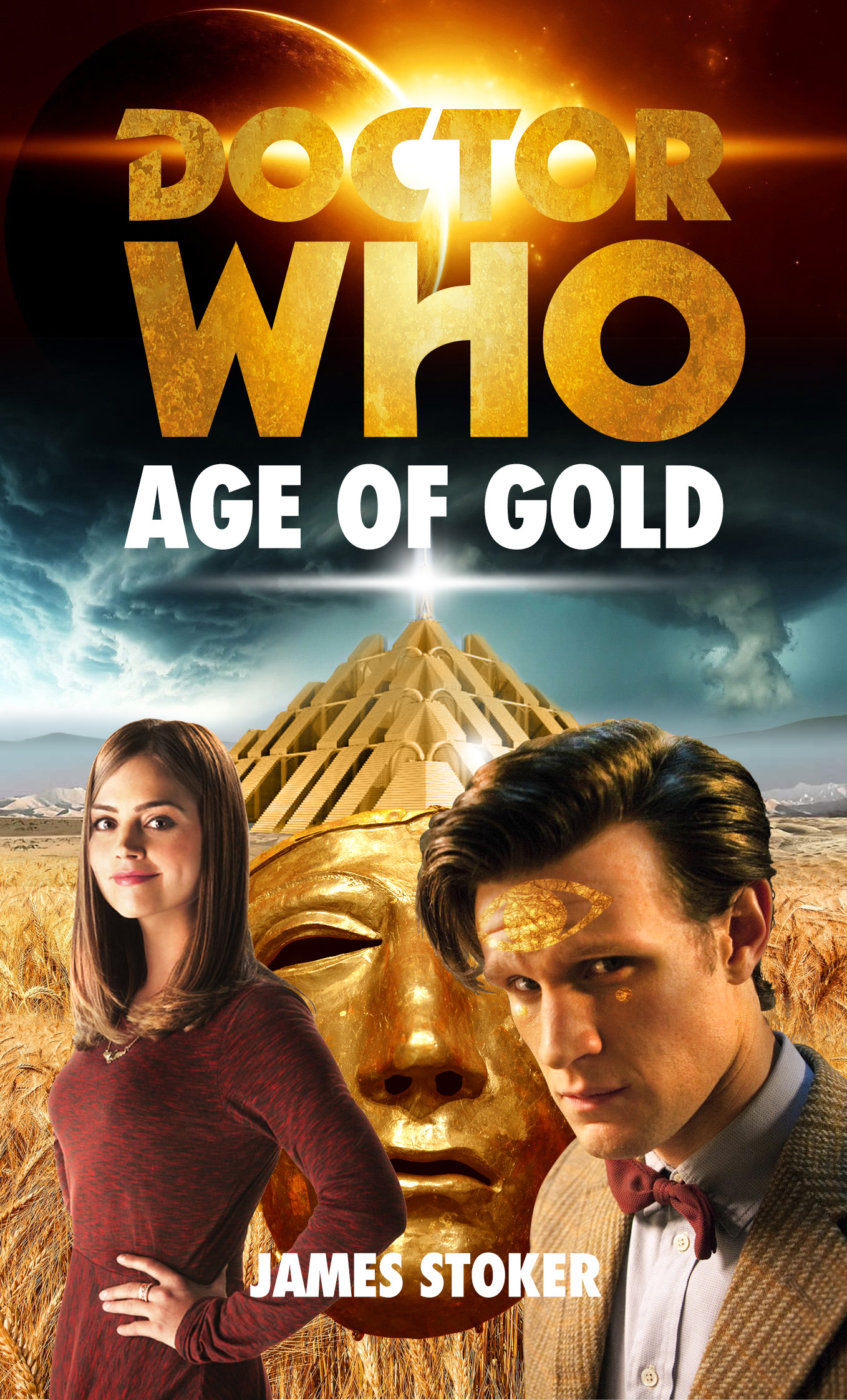

So, here’s Bible Matrix meets Doctor Who by “James Stoker” [3]. Though it starts with some comedy, it’s quite a serious story. If you are up for it, see how many Bible stories, Tabernacle, Covenant/matrix and James Jordan references you can spot. And if you know Doctor Who, watch out for clues. There’s plenty of surprises.

You can download the ebook here. I’ve attempted to follow Truby’s advice: use a familiar format, give the people what they expect, but also transcend the format somehow, which is what the Bible does every step of the way.

And you really must read that book by Alter. So many people think the Old Testament writers were dull primitives, but it turns out that the jokes are so subtle they go right over the heads of most Christians.

__________________________________________

[1] Robert McKee, Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting

[2] This is a great analysis, and very funny. (Thanks Daniel Stoddart)

[3] James Stoker is an anagram of “Master’s Joke,” a pseudonym once used in the show’s credits to hide the identity of the actor playing a recurring villain who was still in disguise.

June 14th, 2014 at 9:15 pm

This is good too

http://youtu.be/HRSz4otyNDM

John Truby on writing for TV

June 15th, 2014 at 11:54 am

Awesome story! Can’t wait to read the rest of it!

June 16th, 2014 at 11:47 am

Thanks – 2 chapters to go.

June 17th, 2014 at 1:00 pm

Listened to some of Truby’s interview. Have you tried matching his 7 step story structure with the Bible Matrix?

http://markmcbride.wordpress.com/2010/05/07/the-seven-key-steps-of-story-structure/

I think the first two (1. Need, 2. Desire) line up interestingly. Need corresponding to creation, desire corresponding to division, or another desire beside the creator’s.

June 17th, 2014 at 3:51 pm

Pretty similar process. I’d say “Ascension” is missing because God’s authority is out of the picture, and his 3-4 are mostly Testing. His 5 is Maturity (mustering the troops). 6 is a mix between maturity and atonement (but of course there is no sin to deal with) and 7 is the new order. I’ve ordered his book where he gives this in more detail as 22 steps.